JoeAnn Hart on Empathy, Quantum Physics, and Separating Pigs with a Broomstick

In the barn and at her desk, Hart works the web of life.

Hello friends!

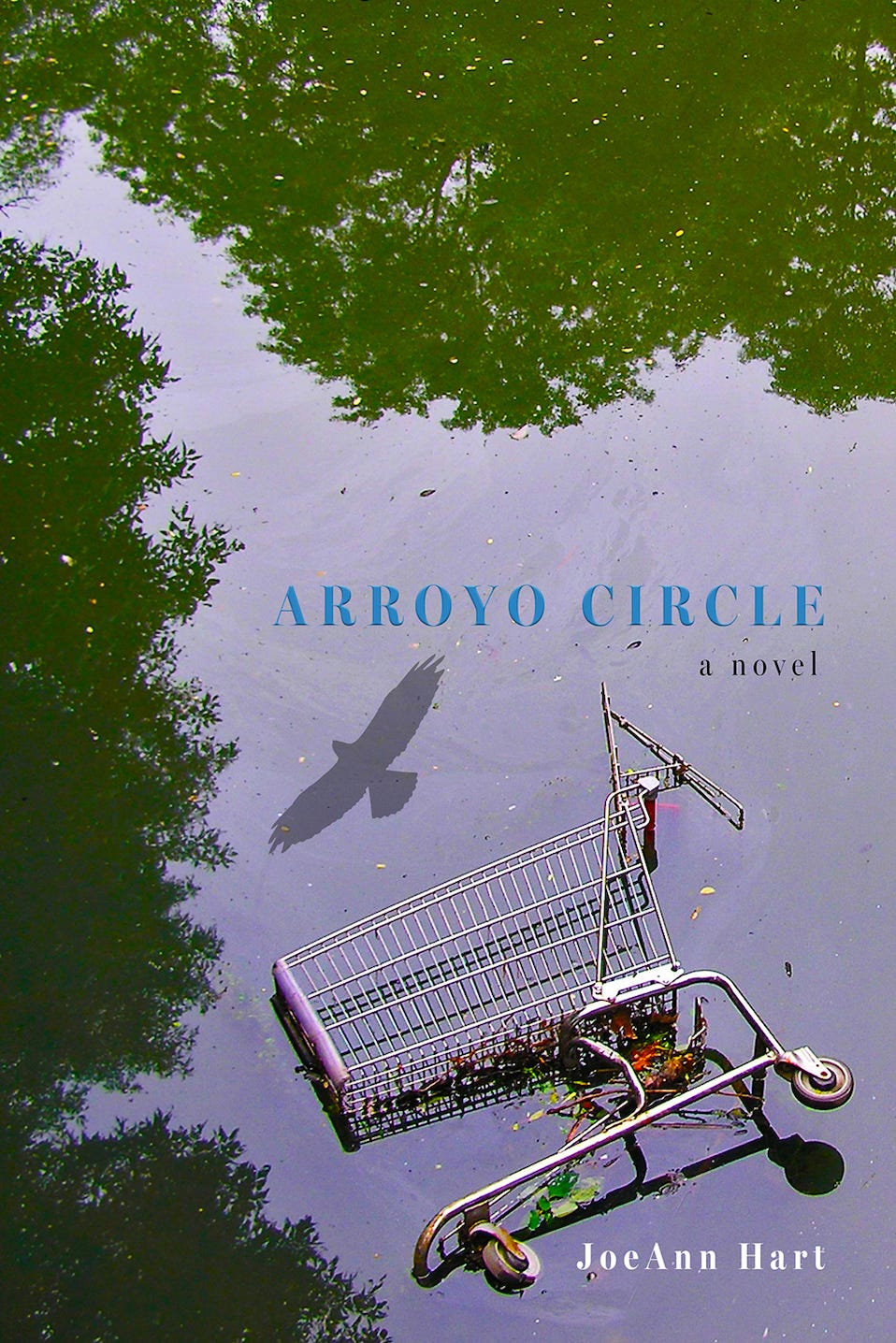

I’m delighted to welcome to Writers at the Well JoeAnn Hart, author of the novel Arroyo Circle, just out from Green Writers Press. Other books include the prize-winning collection Highwire Act & Other Tales of Survival, the crime memoir Stamford ’76: A True Story of Murder, Corruption, Race, and Feminism in the 1970s, as well as Float, a dark comedy about plastics, and Addled, a social satire. Her short fiction and essays have been widely published, appearing in Slate.com, Orion, The Hopper, Prairie Schooner, The Sonora Review, Terrain.org, and many others. Her work explores the relationship between humans, their environments, and the more-than-human world.

Below, Hart describes how multiples losses in her life changed her writing, how she no longer protects her characters from worst case scenarios, and how those very hardships reveal their true natures. For Hart, who rescues barn animals and finds refuge planting sweetpeas, “writing is a meditation unto itself.” Enjoy this deep wisdom from a brilliant writer and thinker.

xo, Tess

What was the seed image (visual, auditory, conceptual) that gave rise to your new book?

There were two elements that came together to spark Arroyo Circle. The first was the death of my brother in 2017. He was a homeless alcoholic for most of his life, and in the depth of my grief I wanted to hold on to him for a while longer, so the character of Les emerged from the mists. My brother was not a scientist like Les, but he wasn’t stupid either, and yet they both lived on the street for one reason or another, and alcohol helped numb their psychic pain. The other element was something that happened to a friend of mine in Boulder a few years ago. She was putting a tub of kitty litter in the trunk of her car in a supermarket parking lot, and someone thought it was a baby carrier and called 911. My friend was pulled over by the police at gunpoint. I’d always wanted to use that story, and so I started Arroyo Circle with that scene, but with the addition of wildfire smoke engulfing the city. In real life, my friend’s event ended with no casualties. In my book, it triggered a series of tragedies.

Can you describe the underground steams that fill your writing well? Are they related to memory, inquiry, desire, something else?

It’s a mystery, isn’t it? I have to assume that my underground streams are composed of my lived experiences, which depend on my memory, along with my dreams, which seem to draw from something else entirely, something dark and deep in the brain. Either way, both memory and dreams are greatly enhanced by my reading life, which is driven by curiosity. Because so much of my writing centers on nature, animals, and climate, I am particularly drawn to science-based books.

Quantum physics, astrophysics, natural history, animal studies, it all goes in the stream, but during the writing process, so much depends on what rises to the surface.

I once thought my memories were fact, but then I started writing a memoir. When my memory stacked up against the journalistic record, I was often wrong. My brain had reshaped my memory because it couldn’t resolve the opposing facts of the murder I was writing about, so now I always dig deeper and rely on extensive notetaking to augment the streams. And then there’s this: The brains of most modern humans are around three times larger than those of chimps but smaller that those of Neanderthals. What are we to make of that? I think that, living with nature, the Neanderthals had to keep the whole of their environments streaming through their brains in order to survive.

How do you access your well? Do you meditate? Walk in nature? Stare out windows?

Sometimes I find that writing is a meditation unto itself, in the way it can block out the conscious mind and let the dreamy images reveal themselves. If that’s not happening, it’s out to the garden and the barn animals, where chores distract my worries so that when I get back to the writing, the images will flow. In the winter, I’ll still putter around outside contemplating where the peas might go first thing in the spring, or where I have to spray again for deer. The outdoors takes my conscious mind out of my interior world, the animals especially. We take in a few rescue livestock, and there is always something to clean in the barn, or some critter needing love. We just took in Snuggles the pig and it’s been a tough adjustment with Iggy, our resident pig, who has not taken kindly to Snuggles. The well fills up quickly when you’re trying to keep two pigs separated with a kitchen broom. And that’s the thing about a well. You have to walk away from it. It can’t fill up while you’re pumping it out during the actual writing.

How has your inner well expanded over time? What experiences, circumstances, landscapes, or relationships have caused you to go deeper in your writing?

Death is a wonderful teacher of life. Pain breaks the heart again and again until it stays open and makes us a better human.

For a long while, I could never give a character a bad end, but once I survived cancer, then lost my father, brother, and best friend in rapid succession, I don’t think twice about it if that’s what the writing calls for.

Death and suffering are just spokes on the big wheel. During this time of loss, I was also dealing with the mental illness of someone close to me. That experience taught me an enormous amount about the fragility of the human brain. Mental health balances on a few cells this way or that. All these experiences have increased my empathy, which is a wonderful asset in writing fiction where you have to spend so much time in the minds and bodies of your characters.

How do ideas and images make their way up from the underground stream and out through the tip of your pen? Can you talk about your process?

One of the most influential books on my writing life was Writing Down the Bones by Natalie Goldberg, where she wrote about how writers have to evade the monkey mind in order to get what is in the well onto the page.

In other words, you have to get rid of the “editor” in your brain, or as Virginia Woolf called it, the angel in the house. You are not going to let your deep thoughts and images onto the page if a part of you is saying that’s not nice, or you can’t say that. Editing can dry up the well before you even get started.

You have plenty of time to edit later, which is a different process, using a different part of the brain. Let’s say I need to start a new scene, and I have an image of what is going to happen, or at least I know how it’s going to start. I give myself a specified time to write and then just start, letting the writing take me where it wants to go and not making corrections or revisions as I go. On re-reading, I am able to see what images and ideas have bubbled up from the mess of a first draft, and then I continue on, learning as I go.

What are you currently drawing up from your well? What can readers expect from you next?

I have been working on a series of short stories set slightly in the future, my first foray into speculative fiction. It seemed a natural segueway from environmental writing and eco-fiction to start thinking about what will happen if we can’t stop runaway carbon in the atmosphere. Several of the stories are already out in the world (Slate.com, Dark Matter, Women Witnessing, The Dodge ) and more are coming, perhaps enough to make a novel-of-stories one day. In these stories, as in Arroyo Circle, things are bad, but they are not hopeless. We can still find joy in life, and we can always work to make things better, no matter how bad it seems. These stories rely a great deal on my research about genetic modification, since in these stories many species need genes from one species to help another species survive and are then rewilded. Evolution can’t work fast enough, but gene splicing can. In this world, there is also an effort to bring species back from extinction, an ethically troubling subject. But if we do not get a handle on the warming world, we ourselves will have to be genetically modified in order to adapt to a new climate.

I understand you are a Unitarian with Buddhist influences. Can you describe the tidal flow between your writing and your spirituality?

A Unitarian comes to a fork in the road. One sign points to heaven and the other to a Discussion about Heaven. The Unitarian goes to the discussion. That’s me. I’ll go to the discussion and then use it in my writing. Unitarianism and Buddhism don’t have Creeds to follow or worship a god. What they have are teachings that reflect on moral codes, and both religions trust the individual to struggle with what it means to lead a good life. In Buddhism, it is understood that suffering is life, and one learns to live with the suffering by cultivating empathy and compassion for all living things.

Working with our hearts and minds is the only thing that’s going to impact the future of this planet, recognizing that all living things are connected to one another. In Arroyo Circle, I work the web of life with literal webs made by spiders, and other circular images, including the street name and title, Arroyo Circle.

In your new novel Arroyo Circle, your character Les is based in part on your late brother Tommy. You say, “I didn’t want to let him go.” Can you describe how transforming him into a fictional scientist affected your inner relationship to him?

Writing is magic in that way. I can create people on the page, even as loosely as Les, and find my self smiling when I write, because I feel my brother in Les. I went into Les’s pain and understood that alcoholism was the least of his problems. It was his friend. During my brother’s lifetime, because of the way he lived and the geographic distance between us, I couldn’t help him, and of course, at a certain point, you realize there is no helping. By the time I finished writing the book, I felt I had opened some of the many gates he left closed.

Les is a cloud scientist who understands quantum physics so well he questions his own existence. Can you talk about the intersection of science and spirituality in your own world view?

The more you read about quantum physics, the more it sounds like a universal religion. It is not just weirder than we think, it’s weirder than we can think. It is mind-blowing, really, what it can say about our sense of reality. Taken to their logical conclusions, most quantum theory becomes wildly illogical, such as this, the Boltzmann brain theory Les mused about in Arroyo Circle;

“Neuroscientists and astrophysicists are priests holding out a promised afterlife in a heaven filled with Boltzmann brains, an infinite number of disembodied minds materializing in the deep future of space, when the intergalactic universe finally expands to the point of dissolution.”

It pretty much sounds like a polished-up version of the Old Testament and must be taken on - you guessed it - faith. Every time I discover some new theory that turns Newtonian physics on its head, my world view is humbled. In the end, it seems that we are so ephemeral and insignificant that we might as well be kind to one another while we’re passing through.

Two characters in your novel suffer from addiction, Les from alcoholism and Mimi from Plyushkin’s disorder. Can you talk about the ways in which a person with Les’s degree of openness and sensitivity might be more vulnerable to addiction? Are there different factors that make Mimi susceptible?

Les is self-medicating his hyper-sensitivity. It pains him to see what humans are doing to the planet, and to know it can be turned around, and we don’t. Or won’t. Scientists on their own can’t take action without political will, nationally and globally. And so, he medicates the suicidal truth of his intense disappointment with the human species. He wasn’t well taken care of as a child either, which might also be why he identifies with the damaged planet. Mimi, who has an unfortunate connection with Jon Benet Ramsey, medicates her many anxieties with shopping. It is what we are all encouraged to do in late-stage capitalism. In some people there’s a glitch in the brain that insists that if buying one new pair of shoes can make you feel better, fifty pairs of shoes must feel great. All of which contributes to climate change.

You say you write in the morning when you are still dreamy. Can you talk about writing from different states of consciousness and why you prefer a more liminal one?

When I am writing an article or essay, any time of the day will do. But fiction writing requires so much from the subconscious, that for me, only the mornings will do. It is a sort of magic getting into characters heads and requires a degree of empathy that is easier to access in a dreamy state, before my mind gets hardened and cynical by the day’s relentless cycle of bad news. Especially lately with the election. These days, by the afternoon, I have no desire to get into any human head. They pretty much disgust me by then, and that’s no way to write a novel.

Your novel explores hoarding, homelessness, and the impact of capitalism on environmental degradation. You say the subject matter is grim, but the book is not. Can you explain?

Hope. I believe our clever species has gotten us in this trouble, but that we may be clever enough to pull ourselves out of it in the nick of time. When it comes to writing with the climate in mind, I don’t do dystopian fiction (okay, one short story). I believe that a novel that centers on climate change, which is very much a by-product of late-stage capitalism, must be frank about what the consequences are for us and the planet, and at the same time hold out hope that it is not too late. Otherwise, why even try to change?

In Arroyo Circle, Les teaches Shelley about the healing powers of nature and the deeper meanings of home. Can you talk about a moment in your life when you found healing in nature? Or when you discovered your own sense of home?

My garden always heals me, and it has since puberty, when I would leave the house in a cloud of adolescent angst and find that as soon as my hands were in the dirt, I’d feel calm. To this day, whether it’s the vegetable garden, or the surrounding fields, or the more structured landscaping close to the house, it is all healing. When I overturn a rotting log and watch the pill bugs waddle to safely, it makes me forget any personal or political problems that have been haunting me, at least for a time. Like Les, the outdoors always feels like home.

I understand you live in Gloucester, Massachusetts, which is one of the most spectacularly beautiful and spiritually imbued coastlines I’ve ever experienced. Did you write Arroyo in Boulder, where it is set, Gloucester, or elsewhere? Does place influence you at the writing desk?

I wrote Arroyo Circle at my desk in Gloucester, where I look out of a window to the harbor beyond the field. It is, as you say, spectacularly beautiful. But as I was writing, my head was in Boulder, which has a very different but intense spirituality. I am not blind to either’s faults, but they are magic places. I lived in Boulder in the late 70s and have returned often over the decades because I have family and friends there.

In one way or another, all my writing focuses on place, because humans act not just with one another, our actions are also interactions with the environment we occupy. It is our context.

Is there anything you’d like to share about Arroyo Circle or your work that I have not asked?

Yes. I’d like to talk a bit about the pandemic in the novel. Writing a novel takes a long time. I started it in 2017 when my brother died and was still mucking about in the first half in early 2020 when the pandemic hit, and the lockdown began. Many novelists were in a tizzy about what to do about it, whether to rework the dates or simply ignore it, but for me, it was a gift. I had already planned for Shelley to have to rent her house out on Airbnb in order to keep it, but with the pandemic, it upped the stakes considerably since she couldn’t crash on anyone’s sofa during rental periods. You really get to know a character when they don’t even have a roof over their heads. You find out if they are a survivor.